We are living in an age of dissolution. Every institution of government and society is in a state of seemingly terminal decline. At the individual level the notions of honour, personal responsibility, and self-sacrifice have largely vanished from public life. The cause of this malaise is not material inequality, but the collapse of faith. The credo of sterile rationalism has triumphed over the metaphysical vision of a divinely ordained world ruled by angels and Gods. For many, the transition from the esoteric world of faith and divine truth seeking to the clockwork universe of the rationalist is vindicated by our cornucopia of material wealth and the unparalleled ease of our lives. Yet is plain to see, for all our prosperity and plenty, the average person remains deeply unfulfilled. No matter the veracity of their nihilistic consumption and hedonistic hoarding, the experience of the modern world is ultimately a shallow and an empty one. Despite all its garish efforts to distract from it, modernity cannot hide the incompleteness it has created by the denial of faith.

It is in fact impossible for the acolytes of modernism to admit to the necessity of faith, because faith itself is incompatible with the primary tenet of today’s anti-faith: an unwavering commitment to total equality. To have a metaphysical belief, to be religious, is to accept that you must subordinate yourself to a higher being – to something outside of, and above, yourself. In doing so you create a cosmic hierarchy; and in following a strict set of moral tenets you exercise discrimination. The sinner thus becomes lesser than the righteous. God becomes greater than the individual. It is these two acts that make faith antithetical to modernity and make its practice a primary existential threat to the modern order. The atheist of today thus screams loudest that no metaphysical world is possible, because he has the most to lose if such an order did exist. He is at once fearful of the collapse of the modern world and its hedonistic pleasures, and simultaneously driven by pathological terror at the idea of being judged by the divine and being found utterly wanting.

It is fundamentally fear that accounts for the lack of true heroism in modernity – a fear of death. A long life is treated as an inherently good life, because the ardent deniers of faith must strenuously attempt to reassure themselves that is the truth. Today’s society seeks to cling to life at all costs. The citizen of today embraces infirmity and avoids danger because if existence itself is the only objective moral criteria, remaining alive is the only true metric of success. What kind of life you lead is irrelevant, only cold utilitarian survival matters. It is ironic that this mode of thought which values only survival has in fact precipitated the gravest danger to the West’s security it has ever faced. In abandoning faith, in retreating into a fear of the great unknown after death, the West has singularly failed to respond to the threat of militant Islam. It is not political correctness that has hamstrung our efforts to repel this new invasion, but our fundamental lack of faith. The burning zeal of a believer will always prevail over the fearful who believes only in living at any cost. The atheist is a slave; the believer is the master.

It can thus be seen both for our personal salvation and to save our way of life we must return to the path of faith. Yet we are the first generation largely to be born without any predetermined spiritual path. We have been totally severed from the great continuum of our native religions. We are thus the first generation presented with the task of choosing a faith for ourselves, rather than simply inheriting it from history as every other generation has. To many traditionalists the solution is simple – we must return to Christianity. In their view, if we all began attending our local church on a Sunday, faith would be restored, and Western civilization would flourish once more. Not only is this a ridiculously parsimonious answer to the complex question of how to regain our faith, it is also an incorrect answer. It does not address the primary reason most of us were driven away from Christianity in the first place: The Church itself. Five hundred years after Martin Luther’s tumultuous revolt against Church corruption and decadence, the selling of indulgences pales in comparison to the scale of hypocrisy, debauchery and outright treachery present in nearly all forms of modern Christianity.

Both spiritually and temporally Catholicism and Protestantism in their modern format are so nauseating it is almost impossible for this new generation of faith seekers to take them in any way seriously. The Catholic Church – once the bejewelled repository of European faith – is now reduced to a shadow of its former self, more associated in the popular imagination with paedophilia than spirituality; and headed by a Pontiff who is more concerned with kissing refugee’s feet than engineering a resurgence of the European spirit. Protestantism fares no better. European national churches which have always been wedded to the zeitgeist of the state have simply joined modernity’s war on faith. In their Evangelical and American form, the Protestant faith is reduced to little more than an activity group, a superficial faithstyle choice which has no serious capacity for esoteric knowledge and searching for divine truths. The nouveau branches of Christianity such as Mormonism and the Jehovah’s Witnesses seem almost as alien to the European spirit as Islam itself.

It is undeniable that the political influence of the Church has been harnessed in almost every occasion against the traditionalist world view – whether supporting mass migration or lending its support to regimes beyond our shores. The reason for this is that at the heart of modern Christianity, the doctrine of universalism has been placed on a pedestal above all other values; and universalism is in actuality simply a euphemism for the total equality of atheism. It is for this reason that flocking back to our local Church will neither enlighten us nor shield us from the ravages of modernity – it will merely grant legitimacy to another tainted, destructive force and add voices to the deafening chorus demanding more equality, more nothingness. Faced with the seeming irredeemable nature of modern Christianity, an increasing number of spiritual nomads have decided to take their quest to an earlier, more primordial form of faith. Perhaps we do not need the return of God, but the return of Gods.

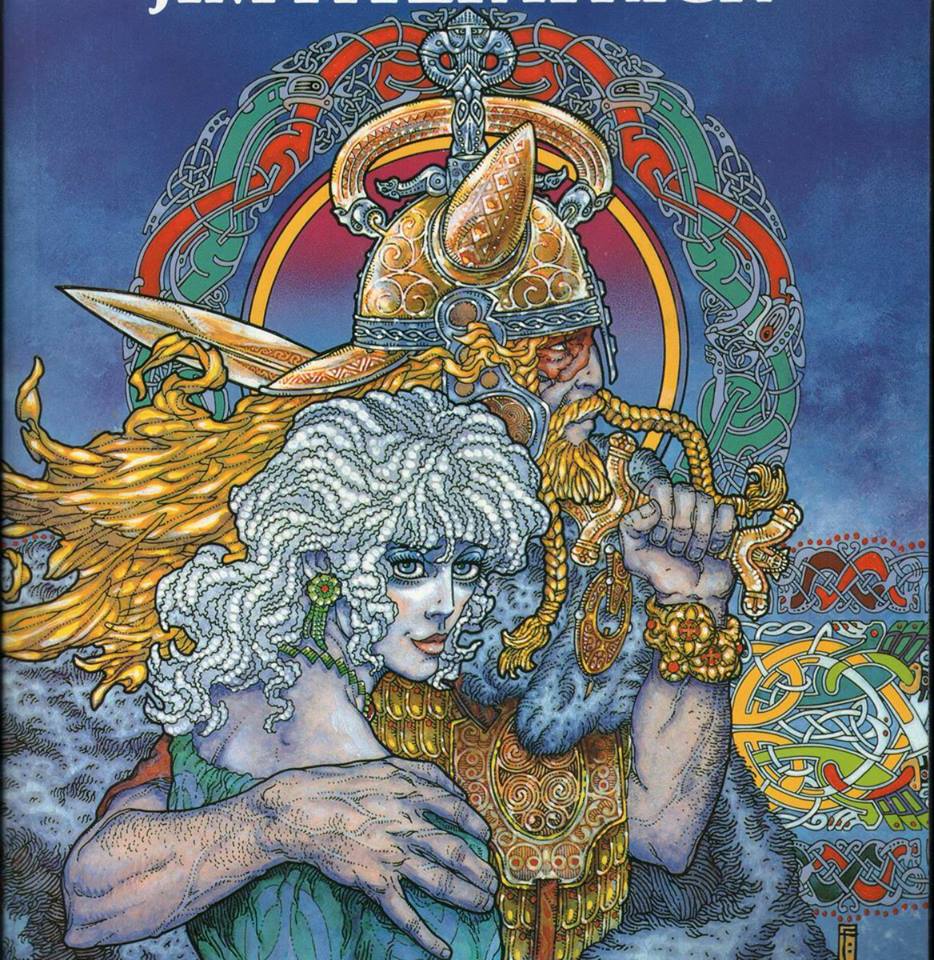

The neo-Pagan revival which is underway in many parts of Europe is fuelled by a wholesale rejection of Christianity as a proto-modernist credo which usurped the true faith of Europe. Certainly, Paganism has many attributes which lends it to be seriously considered as a possible solution to our modern predicament. In an era which is increasingly barbaric, the revival of the Gods of war, strength, and honour seems a welcome and necessary step. The inherent fluidity of divinity in Paganism – the notion that Gods walk amongst us, and that we ourselves may attain a modicum of divine power provides the mechanism by which Paganism can turn life itself into a heroic adventure. Just as in Wagner’s epic Ring Cycle it was Siegfried who was the embodiment of divine heroism, by reconnecting with the Pagan Gods of the past we too can transform our lives into an epic saga as we seek self-mastery and to both revere and chafe against the divine hierarchy.

Thus, by accepting Wotan into our hearts, while the average person drowns helplessly in the slime of modern life, we soar above them as we are carried on the wings of Valkyries. Paganism is an antidote to the timid veneration of luxury and safety which has replaced faith in modern life. A man who believes he will cross the Rainbow Bridge to join his Gods and comrades in the vaunted halls of Valhalla is not paralyzed by the fear of death and therefore is not acquiescent in trading his freedom and integrity for a few more years of the easy life. While the huddled masses view the impending clash of Western and Islamic civilization as a disaster, the pagan relishes it as a chance to attain honour and glory – the pagan revolt is truly a total inversion of modern values which enjoins the strength of the Gods with a personal quest for self-betterment.

Yet while this appeal to heroic individualism may captivate some – more serious-minded faith seekers have their reservations. It is certainly true that Paganism creates a hierarchy and reignites the metaphysical, but it at times can seem a narrow, limited faith system which has little space for the monastic intellectual, esoteric, and spiritual truth seeking which Christianity once provided. To return to Paganism would naturally entail the regression of certain aspects of civilised life we have come to enjoy for centuries, and its kinetic nature is seemingly incompatible with fixed stability. It may prove, at best, to be a temporary solution to our crisis of faith. After all, Paganism was washed away once by Christianity, and it is perhaps possible that a reformed Christianity could provide an even greater dynamo for our spiritual revolution. It is true that almost anyone that enters the great cathedrals of Europe can still hear the faint whispers of God.

The very success of Christianity has always been its ability to be reinterpreted and reformed. It has provided the impetus and driving force for Western civilization because its schisms, its doctrinal disputes, its interminable and blood drenched civil wars have kept Western civilization vital and have driven it onwards to ever greater heights of aesthetic and doctrinal beauty. When Luther launched his withering attack on Catholicism, it responded not by timidity and acquiesce – but by launching the greatest programme of artistic and intellectual prowess the world had ever seen: The Counter Reformation. Just because almost all Christian churches of today are weak-willed and unfit custodians of the faith, it does not mean the faith itself is the problem. On the contrary, Christianity can also provide a framework for man to ascend the golden path and leap from the gutters of modern life.

The most useful example of this is to take seriously the notion of St. Peter and his eternal watch over the Gates of Heaven. It is pertinent to always ask yourself the question, could I justify myself to Him right now if I died? If the answer is no, then it is time to revolt against the materialistic considerations of this life, and prepare instead a life worthy not of the judgement of your self-absorbed peers, but one which holds up to Divine scrutiny. It is this test of St. Peter which so terrifies the nihilists and atheists of modernity, who in the dark recesses of their mind know that if they are wrong, if their conduct in life was ever set against any objective test of morality, they would fail. This vision of St. Peter’s judgement becomes all the more powerful when we view Christ not as the meek, hapless Shepherd he has been portrayed as by the modern Church, but as Christ the destroyer of evil, vanquisher of the moneylenders, Christ the morally inflexible, crucified and whipped because he would not renounce his views or his mission. Once we view Christianity as an armour of faith which lends its power to our cause, we reconnect with the muscular Christianity that inspired the Templars, turned back the Ottoman’s at the gates of Vienna, and can now traverse the chasm of lost confidence we need to restore Western civilization. Once we accept our task as being able to look St. Peter in the eye and say with total honesty that we fought for the good, then we are no longer simply the agreeable Anglican or mildly contrarian Catholic. We have moved our frame of reference from the worldly to the divine – we have become Knights of Christ.

A case then has been made for both Western Christianity and Paganism being the true faith which can revitalise both the individual spirit and Western civilization itself. Yet the question which preoccupies many of a traditionalist persuasion, is how do I choose – Paganism or Christianity? In a world of inherited religions, this question would have never arisen. Yet in our modern situation it can become a serious philosophical stumbling block. And this is without speaking at all of other alternatives – of Eastern Orthodoxy, of a Nietzschean transcendental quest for self-betterment, or of the elevation of nation or nature to the place of God. Thus, how can one choose between one faith or another? By what criteria can we decide?

That is fundamentally the wrong question. We must understand that we live in an aspiritual age – that we have been conditioned from birth to reject faith in all its forms. We are in the position of the barbarians of the dark ages who slowly came to understand the ruins they were huddled in were not made by God, but by men. We are at the very beginning of the process of relearning what faith is, of understanding what the world of religious sites we have inherited mean. We must at this stage merely examine, and attempt to understand the religious heritage of Western man. We must straddle the dualistic, even contradictory nature of our faith. We must become Men of Janus who understand that Western man was both the Roman, and the Gaul. He was both the Viking, and the Templar. The Men of Janus understand that in the quest to save themselves and Western civilization, the final reckoning will be decided by how many faithful stand against the indifferent. By exploring faith, by studying religions, by re-learning spirituality we will come to know what appeals to us, which god speaks to us, and in the end – how we can escape the spiritual wasteland we find ourselves in and finally free ourselves from our fear of death and what awaits us.

Recent Comments